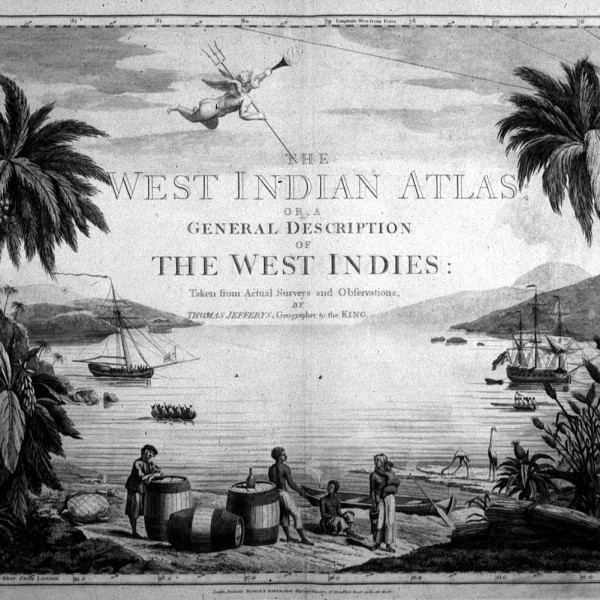

Eugenics is a now widely discredited method of selection of “highly-rated” or “desirable” genetic qualities in an attempt to speed up the evolution of the human race. The term was coined by explorer and natural scientist Francis Galton in 1883, but the concept can be seen as early as 1853 in Charles Darwin’s On The Origin of the Species.

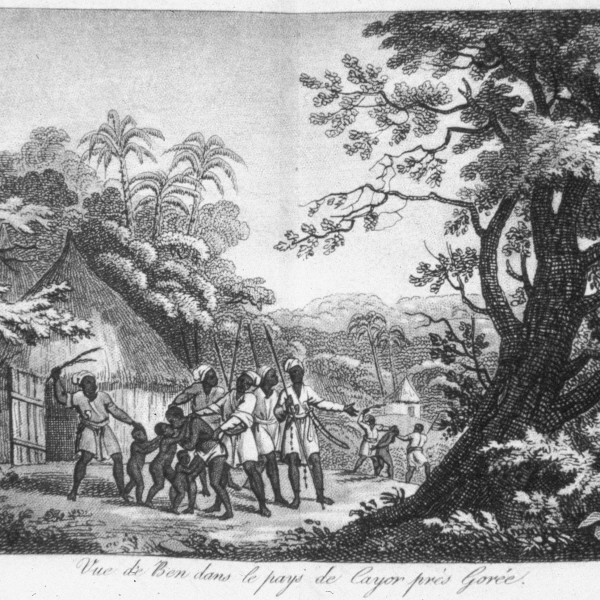

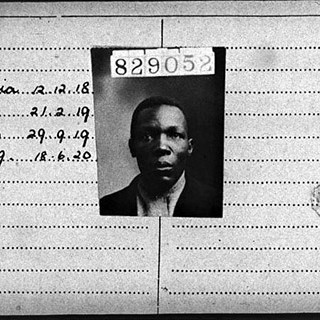

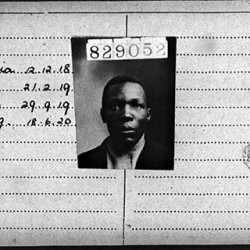

Racism has been alive and well in society since long before the arrival of eugenics, but it was this concept that allowed for the rampant structural, institutional and “scientific” oppression of what were considered to be inferior races. Historically, this injustice has led to Black bodies being brutalised in numerous ways, from forced sterilisations, to using Black people for medical experimentation and drug trials.

During the second world war, the Nazis used eugenics as a foundation for many of their beliefs and to justify the genocide of millions of people. Since then it has been widely discredited and considered a non-science. But before this point it was the basis of numerous laws, policies, abuses of power and prejudiced mindsets in the U.K. and in the United States. The greater implication of this is some strong ideological similarities between the U.K., the U.S.A., and Nazi Germany. Both countries have since worked hard to erase and ignore this upsetting likeness.

Today, we can see the effect of eugenics in the fact that most of the media we consume presents white, European features as the most desirable. Typically Black features, like full lips, and curvy bodies are seen as undesirable or ridiculed, unless worn by white people. It’s also visible in lingering stereotypes that Black people are uneducated and unintelligent, as well as in medical settings in which Black patients are dehumanised, seen as less sensitive to pain, and experience greater brutalisation in encounters with authorities.

Previous Story

Previous Story