Elizabeth Heyrick (1769–1831) was a slavery abolitionist, social activist and philanthropist.

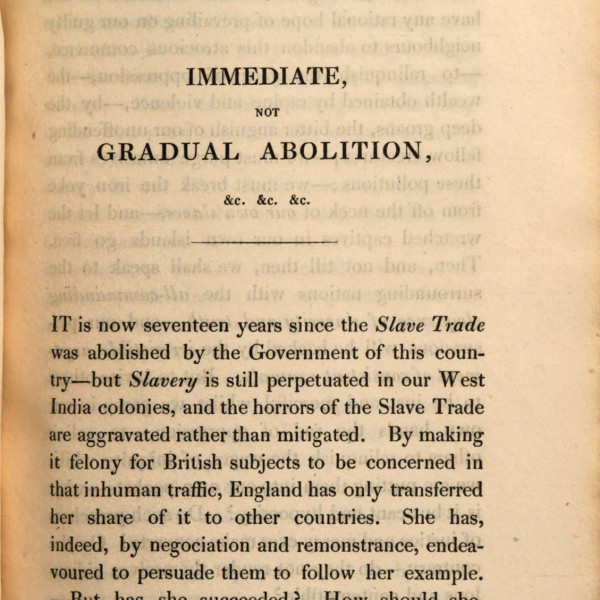

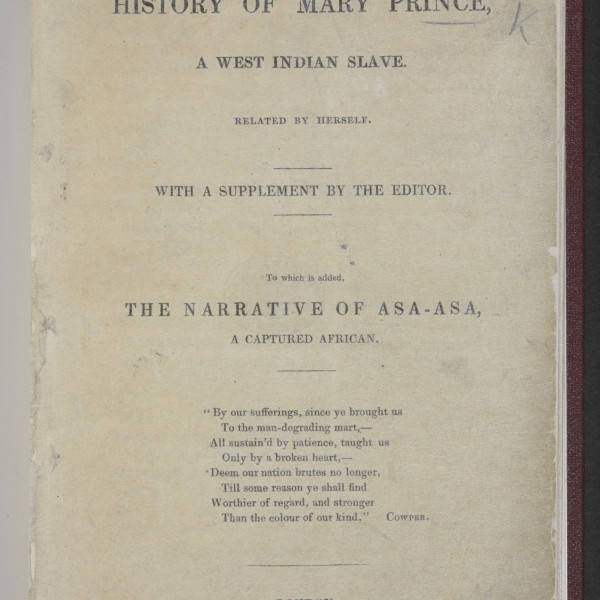

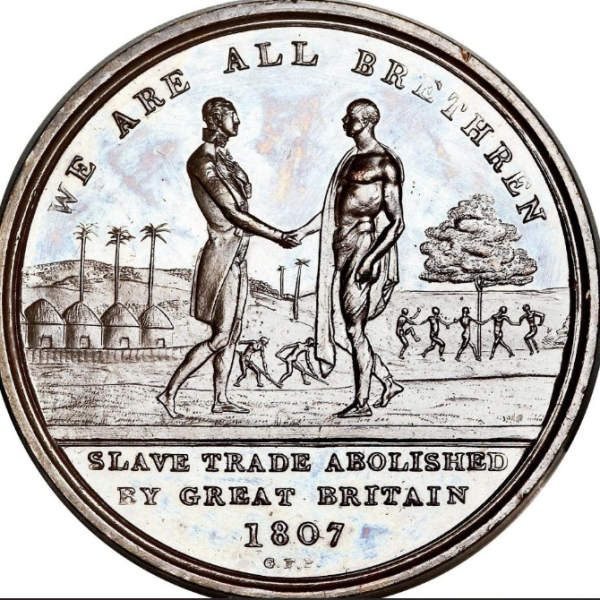

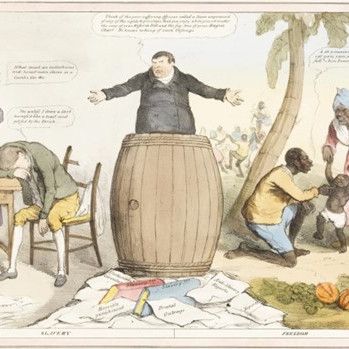

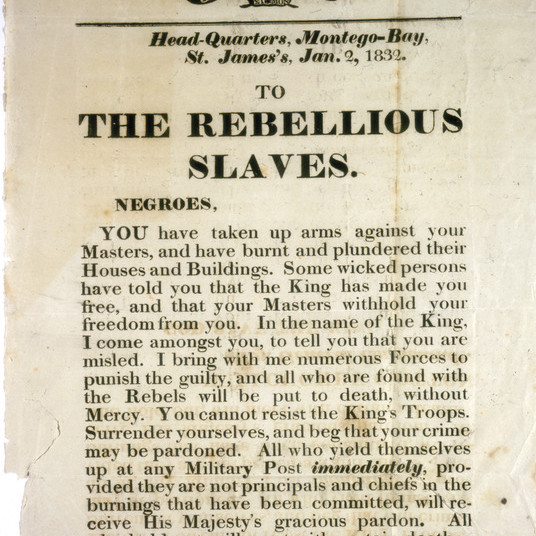

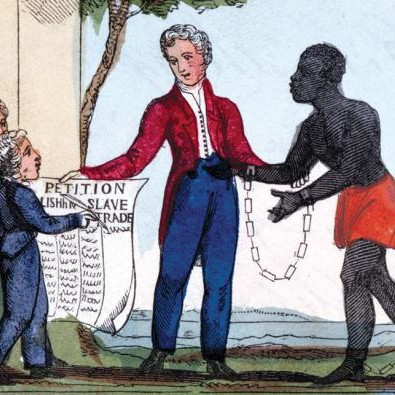

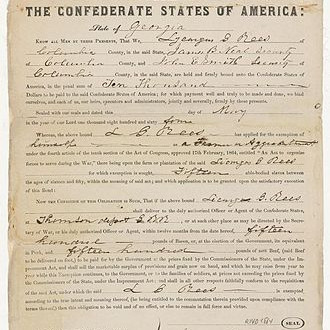

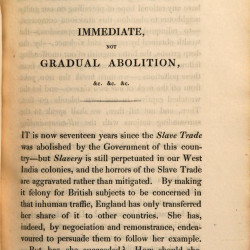

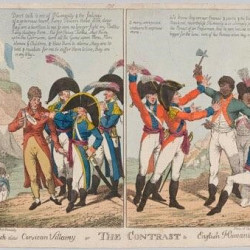

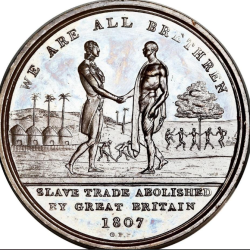

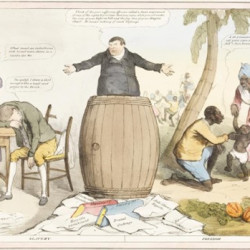

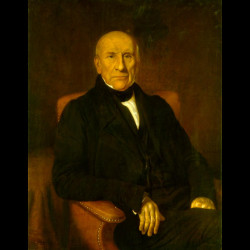

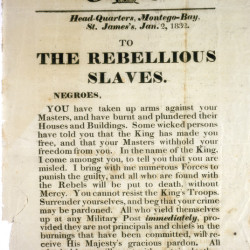

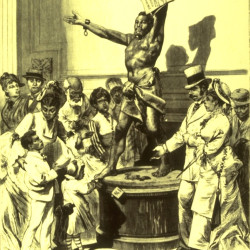

Her pamphlet Immediate, not Gradual Abolition (1824) criticised leading anti-slavery figures of the time for being too "polite" and “accommodating” of plantation owners in the Caribbean. Heyrick campaigned for the immediate abolition of colonial slavery, rather than the gradual approach favoured by William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson and other abolitionists after the abolition of Britain’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade in 1807.

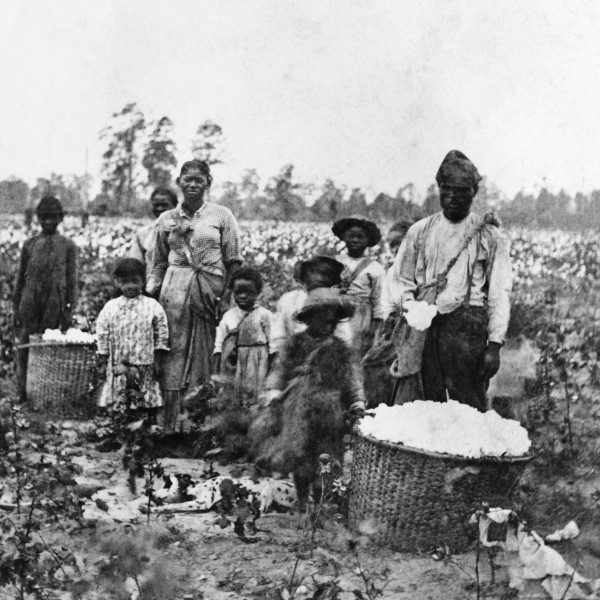

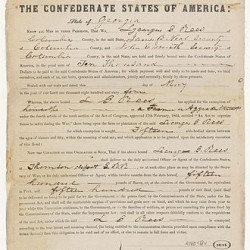

Heyrick was born in Leicester to dissenting parents. Following the death of her husband John died in 1797, she became a member of the Society of Friends and dedicated herself to writing and activism. Heyrick’s overriding passion was for the abolition of slavery in the British colonies, something she believed, ‘in which we are all implicated; we are all guilty.’

Immediate, not Gradual Abolition was widely distributed at anti-slavery meetings across the UK in the 1820s and was influential in shifting public opinion to support the cause of abolition. The pamphlet also sold thousands of copies in the USA.

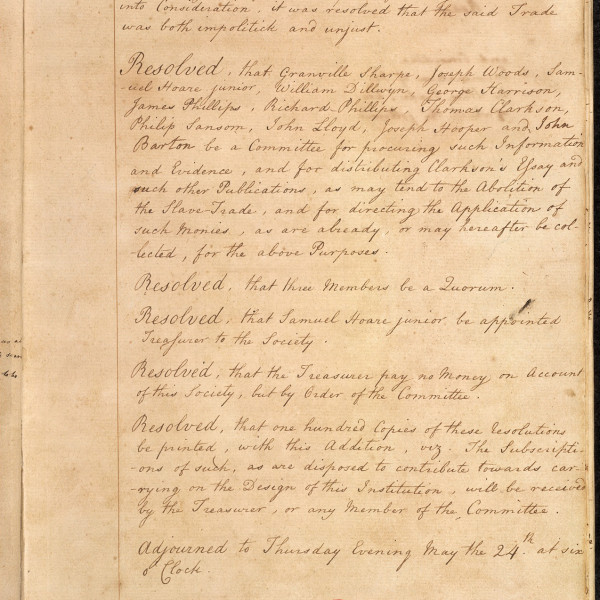

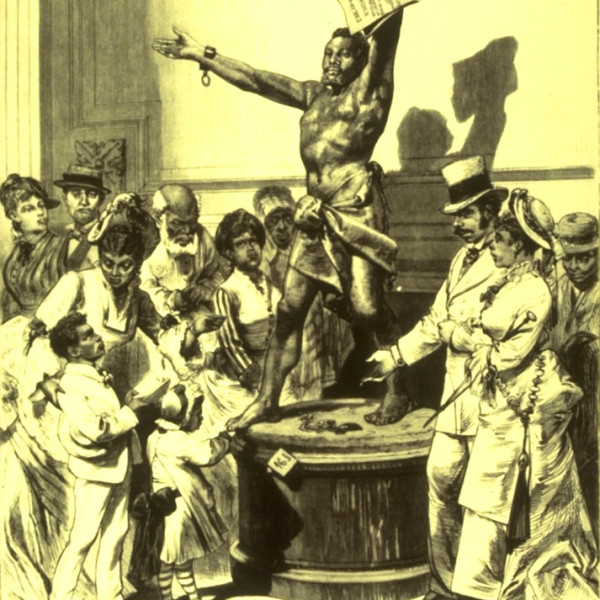

By 1830 there were more than 70 women’s anti-slavery societies in existence and they became an influential force in the abolitionist movement. Heyrick died in 1831 and therefore did not witness the passing of the 1833 Slavery Emancipation Act.

Previous Story

Previous Story